| |

|

|

Robert Wyatt Reflects on the Making of ’68 - Downbeat.com - April, 26 2014 Robert Wyatt Reflects on the Making of ’68 - Downbeat.com - April, 26 2014

ROBERT WYATT REFLECTS ON THE MAKING OF '68

|

|

In his almost 50-year career, British multi-instrumentalist Robert Wyatt has been involved in a stunning variety of projects. His recently unearthed album ’68 (Cuneiform Records) is a four-song psychedelic journey, recorded in 1968 in Hollywood and New York. Wyatt used studio space provided by guitarist Jimi Hendrix and multi-tracked his parts on piano, organ, bass, drums, percussion and vocals. One song, “Slow Walkin’ Talk,” even features Hendrix on bass.

Wyatt first came to prominence in the late ’60s on both sides of the pond as a founding member of the band Soft Machine. In 1968, the group opened for The Jimi Hendrix Experience for two extensive tours in the U.S., and later that year Wyatt began recording the demos and musical sketches that would eventually become ’68.

In the years that followed, half of the album surfaced; the other half, thought lost until recently, has been brought together with the other material for the first time and is now available on CD and limited-edition blue vinyl (a white vinyl version of the LP has sold out).

In recent years, Wyatt has worked with contemporaries like saxophonist Evan Parker, the Sigamos String Quartet, trombonist Annie Whitehead and the always mercurial Brian Eno. His 2010 collaboration with saxophonist Gilad Atzmon and violinist Ros Stephen, ... for the ghosts within’ (Domino), mixes standards and original songs, illustrating Wyatt’s idiosyncratic way of bringing different musical worlds together.

Wyatt recently spoke with DownBeat about his lifelong interest in jazz, as well as the creative period that produced his 1968 sessions.

DownBeat: In 1968, you went into studios in both Hollywood and New York City to record some demos, creating sketches that would eventually include two long suites. And now we have ’68.

|

| |

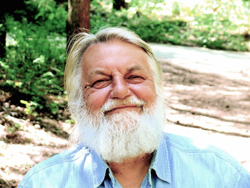

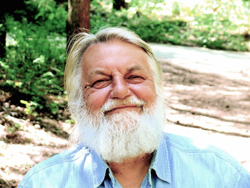

Multi-instrumentalist Robert Wyatt has an idiosyncratic way of bringing different musical worlds together. (Photo: Alfreda Benge) |

|

Robert Wyatt: I don’t know about the importance exactly, but it certainly took me by surprise to hear it all. I hadn’t remembered how much I’d obviously worked over the material before it emerged in public in the following years. I’m relieved to find that, if anything, I erred on the side of spontaneity during these forgotten—by me, at least—workouts.

DB: What about working with Hendrix and his playing at these sessions?

RW: I do, unsurprisingly, remember that I was awestruck by Jimi Hendrix. We’d heard him play night after night on those long tours around North America. He was much more considerate of his audiences than his public image suggests, a real professional who wanted to make sure that even the listeners far at the back of the venue got their money’s worth. In some ways, he was even too modest. For example, he didn’t rate his own wonderful singing … “Somebody’s got to do it” seemed to be his attitude! So shy, behind the pyrotechnics. But every single time he dropped the tempo to sing, “There’s a red house over yonder,” it brought tears to my eyes. I was thunderstruck when he dropped in on my demo sessions to lay down a bass line on a little blues track I was recording, Brian Hopper’s “Slow Walkin’ Talk.” I was so grateful that my modest attempt was so magically enhanced by his presence. I should add: This has only become apparent thanks to the conscientious cleanup work on the original dusty acetates by Canadian Mike King.

DB: This was your first real solo outing.

RW: After the tour, I stayed with the Experience in Los Angeles, in a rented spread in Benedict Canyon. Hendrix had hired a studio complex nearby, with more capacity than he needed, so he invited me to use a spare studio to try things out. I had no group around by then, and used the opportunity to work alone on new material, multi-tracking on drums, voice and the instruments available—piano, organ and the occasional bass guitar. Hendrix, perhaps taking a break from his own work, dropped by one day to see how I was getting on, offering to play some bass on the thing I was working on. When I returned via New York back to England, those recordings got lost in the shuffle—only to have been unearthed recently. Steve Feigenbaum, who had already released some of my retrieved experiments on his adventurous Cuneiform label, took on the task of having those recordings cleaned up and released. So, ’68: The title refers both to the recording date and to the funny coincidence that it was released last year, when I was, in fact, 68.

DB: How did Soft Machine approach the studio?

|

| |

Robert Wyatt’s ’68 (Cuneiform) was recorded in Hollywood and New York and features Jimi Hendrix on one track |

|

RW: The combined sound was not predetermined. It really did become a journey into uncharted territory. To this day, when I invite musicians to help me make a record, it’s their uniqueness that I want. I still like to celebrate the special character of each participant. That may be why, even when I’m starting off with a simple pop-song framework, the result rarely fits into some preordained marketing category.

DB: In the July 11, 1968, issue of DownBeat, contributor and musician Mike Zwerin covered the emergence of Soft Machine with a band interview and story. What do you remember about Zwerin the writer?

RW: Michael Zwerin, who became a great friend, was an expat working for the International Herald Tribune in France, and had seen [Soft Machine] play in St. Tropez. He also took me to lunch with the wonderful saxophonist Paul Desmond, which was, for me, a mind-blowing occasion. I think Mike was maybe just relieved to meet a British rock musician who loved jazz.

DB: John Coltrane was a big influence then, and still is.

RW: The year Soft Machine was launched was the year John Coltrane died [1967]. Saint John, as far as I’m concerned. And I’m reminded of what happens in the forest when a really giant tree falls. Suddenly, there’s a clear patch in the undergrowth, where lots of little saplings busily take over the space, hurrying towards the sunlight: life reaffirming itself. But such giant trees don’t spring up overnight. So our emergence into the sunlight was always haunted, in my mind, even in the irreverent gush of youth, by the incomparable beauty of what we had lost.

John Ephland

|