| |

|

|

The

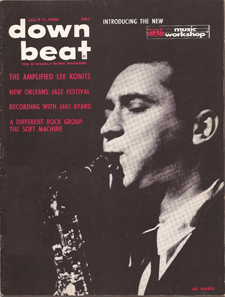

Soft Machine - Downbeat - July 11, 1968 The

Soft Machine - Downbeat - July 11, 1968

THE SOFT MACHINE

|

|

By Mike Zwerin

THE SOFT MACHINE IS the world, a woman, a book by William

Burroughs -or a psychedelic pop group from London. Whatever

it is, it recently toured the United States as part of a

package with the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Enveloped in Mark Boyle's moving, abstract projections,

floating in many colors on top of them, the Soft Machine

presents quite a sight onstage, though not an unusual one

in our time. They wear the accouterments expected of the

prototype-shoulder-length hair, hats from thrift shops,

tiny dark glasses, paisley shirts, beads and bells. Drummer

Robert Wyatt sometimes plays dressed only in a bikini bottom.

In short, they look like three freaky dropouts.

Things are not always as they appear. Organist Michael Ratledge

went to Oxford on a scholarship, winning the college prize

in philosophy in 1964 and later taking his honors degree

in psychology and philosophy. He describes himself as having

a "cool but absent mind... I'm very much the kind of person

who does what's there. I'd planned to do graduate work in

American poetry, of all things, but l applied too late for

the grant. The same day I learned it was lost, a lady friend

of Kevin's (Kevin Ayers, the group's third member) gave

him her mink coat. We sold it, bought an organ, and started

an avant-garde jazz group. But London wasn't ready for us

yet. Then we found we could play the way we wanted, call

it 'pop', and have a chance to be heard.

" Robert's parents are liberals, old friends of Robert Graves.

He spent two summers as Graves' house guest in Deya, Majorca,

and the poet and novelist is something of a hero to him.

Robert smiles easily and well.

Although

the most outlandish dresser of the three he is not unconscious

of the bag it puts him in or of his impact on "squares."

"I had a hard time deciding about my hair-had it cut

a couple of times. Any kind of uniform bothers me. But when

I saw the Rolling Stones for the first time, I decided I

just wanted to look that way, regardless. We have been cal!ed

a 'psychedelic' group, which implies we all take acid....

and that turns us into some kind of sideshow. I resent that.

What I do, I do myself. I don't need any drugs to play the

drums."

Kevin Ayers is more like what coud be cal!ed hippy. On the

group's press release, he is described as follows "...

vocals bassguitar leadguitar songwriter arranger illustrator

poet eater. Born Herne Bay U.K. 1944 (Leo) educated Singapore

and Chelmsford Essex height 73". Left school early

and hung about London Canterbury Canary Islands Casablanca

Majorca writing his songs en route. Has the gift for writing

most commercially magical songs. (A boy but wild when moody.)

..."

Kevin is also soft-spoken and lucid. "Our music,"

he said, "is just an extension of what we were fooling

around with when we were all living together in Canterbury.

It's the way we prefer to spend time, rather than p!aying

cricket or golf. The fact that we are working, earning bread,

is kind of accidental. When we play concerts, we don't think

about things like pleasing teenyboppers. Our music is different."

How is it different? We were all in his small room in New

York City's Wel!ington Hotel on Seventh Ave., the 6 o'clock

news going unwatched on television. Kevin was stretched

out on the unmade bed, his face half covered by silky hair.

He propped his head on one band and thought for a few seconds.

"I guess it's because it isn't based on the blues,

really. We kind of stay away from those familiar patterns.

That's probably why we haven't made it yet. Managers are

only interested in 'can they make money.' I think this tour

may have started ours thinking maybe we can. The audience

response has been fantastic."

|

|

ONE OFTEN HEARS about young pop groups making fortunes

but rarely about the others. When I first met Michael, Kevin

and Robert last summer, they were pretty much stranded on

the French Riviera. Along with two road managers, they had

crossed from London and driven to the Riviera jammed in

a panel truck full of electronic hardware. They were scheduled

to work all summer as part of the "beer festival"

on the beach of St. Aygulf. After a week, they were fired.

It seems the wrong element (penniless) was hanging around

the discotheque but not drinking beer.

Then the trio floated around St. Tropez for some time, sleeping

on floors or the beach. Finally, Jean Jacques Lebel hired

them to be the second half of his Festival Libre, and they

performed each night after Pablo Picasso's play, Desire

Caught by the Tail. It was a good time, but as is so

often the case, they were paid in inverse proportion to

their enjoyment of their own music.

So far they have invested more than their salary in amplifiers,

speakers, guitars and other such things. A new level of

affluence was reached on the tour of the United States:

$100 a week. Out of that, however, they paid Boyle because

they feel his projections are essential, an opinion their

management doesn't share.

Michael has written a scholarly paper on Boyle. "Mark

Boyle's 'events' are content with a direct presentation

of the reality that already exists, with no self-interposition

from the artist... Whereas 'happening' implies agency, 'event'

is the effect of something happening; to perform a 'happening'

it is necessary to act, but one cannot act an 'event.' It

is sufficient to realize the fact that a 'happening' has

occurred. An 'event' is a discovery of what is happening,

a 'happening' an active invention-fact as against act."

Boyle, a Scot with a melodious brogue and establishment-length

hair, has eyes that blaze with warmth and involvement. He

explains himself:

"The most complete change an individual can effect

in his environment, short of destroying it, is to change

attitudes to it. This is my objective...

|

I am certain that, as a result, we

will go about so alert that we will discover the excitement

of continually digging our environment as an object/experience/drama

from which we can extract an esthetic experience so brilliant

and strong that the environment itself is transformed."

In 1966, Boyle obtained sophisticated projectors that made

possible his most ambitious "pieces" entitled

"Earth, Air, Fire and Water," and "Bodily

Fluids and Functions." In the latter, human body fluids,

such as blood, saliva, bile,vomit and sperm were projected

onto a large screen together with electroencephalogram and

electrocardiogram responses of a couple making love, while

the sounds of the bodies were amplified throughout the auditorium.

Although his projections over the Soft Machine are somewhat

more modest, they add an exciting visual dimension to the

music. Unlike most other light shows, he uses no stills

and no objective images of any kind. The light and movement,

formed by liquid chemicals, are determined by chance factors.

Michael writes, "... These presentations make it possible

for the spectator to rediscover the 'esthetic' aspect of

our environment that has become hidden by accretions of

use and habit and to become aware of... environments that

were previously inaccessible to us."

The Soft Machine is not part of anybody's musical establishment.

The jazz establishment will not accept it because of the

rock format, instrumentation and appearance. At the same

time it is not commercial enough for the pop world. And

although composer Earle Brown loves the group - he may write

a piece for it - "serious" musicians right now

don't consider this sort of thing legitimate.

Despite occasional lack of control and a tendency to extend

length beyond content, the Soft Machine is unique and satisfying,

an impressive synthesis of various elements from Karl-Heinz

Stockhausen, John Cage, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, and

rock itself.

Its cloudy sound moves to unexpected places in weird ways.

Everything is filtered through a fuzz box, an electronic

gadget that intentionally distorts sound. (For an example,

listen to the introduction of the Rolling Stones' I Can't

Get No Satisfaction.) There is a good deal of collective

improvisation. Sets are more like suites, each 'tune"

running into the next. Unlike most rock groups, the Soft

Machine makes crescendos and decrescendos and incorporates

silence.

I have never heard (or seen) any thing quite like it.

|