| |

|

|

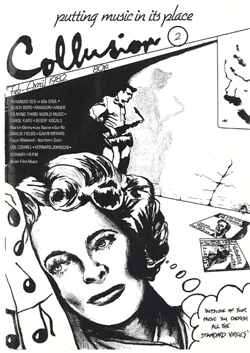

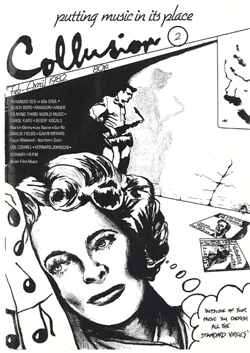

East / West - Collusion - #2 - February-April 1982 East / West - Collusion - #2 - February-April 1982

|

|

|

Hannah Charlton looks at the story behind Bengali group Dishari’s entry into the singles market - a collaboration with Robert Wyatt on Rough Trade.

Flipping through a stack of singles released over the summer of 1981, you might just pass a greeny-turquoise image of grasses with, high at the top, the small pink titles Robert Wyatt/Grass and Dishari/Trade Union. But this discreet cover disguises a quietly momentous record, Not only is it an unusual combination, but it also pinpoints a number of issues to do with cross-cultural productions, their presentation and understanding.

The first song is an Ivor Cutler composition, ‘Grass’, arranged and sung by Robert Wyatt with the beautiful tabla playing of Esmael Shek masking the underlying violence of the words. The second is a unique song called ‘Trade Union’ by an East End Bengali group, Here the words are paramount — if mainly to the Bengali community in this country. Rough Trade, with great open-mindedness and enthusiastic support for Robert Wyatt, released the record but perhaps underestimated the careful thinking involved in presentation, distribution, marketing to make the Bengali song much more than a novelty under Robert's wing.

For the single is a two-sided affair, aimed at two audiences who share little contact — the Bengali community and Rough Trade record buyers. They listen to music in different places, they buy their records in different shops... and yet, here is a curious bridge which may lead to a bit more understanding about different musics and the way they function. We live in a pluralist music culture where many musics are out-of-bounds or deliverately not available to the public at large. An example of the latter is the music of feminist bands who play to women-only audiences. Sometimes these musics may be private in the sense that they have strong significance for a small number of people (early music, improvisation) and mostly they operate outside the confines of the music industry and press.

STRANGE FRUIT

The story of how this record came about goes back to 1979 when Robert Wyatt attended an AARF (Artists Against Racism and Fascism) event and was struck by Dishari’s music. After meeting them he suggested that they record ‘Trade Union’ on one side of the last in a series of singles he has put out over the fast year. This series includes Robert’s versions of ‘At Last I am Free’ and ‘Strange Fruit’. ‘Stalin Wasn’t Stalling’ (a ‘40s acapella number originally recorded by the Golden Gate Quartet) is coupled with Peter Blackman reciting his epic oeuvre of Stalingrad. So, by single number four, the inclusion of ‘Trade Union’ was not incongruous — preceding material having been so wide-ranging. It was also a great recording opportunity for Dishari.

COUNTING THE WAVES

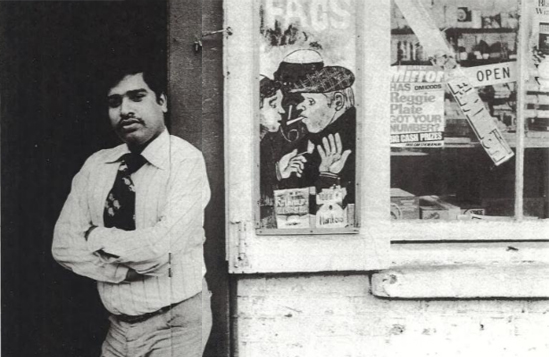

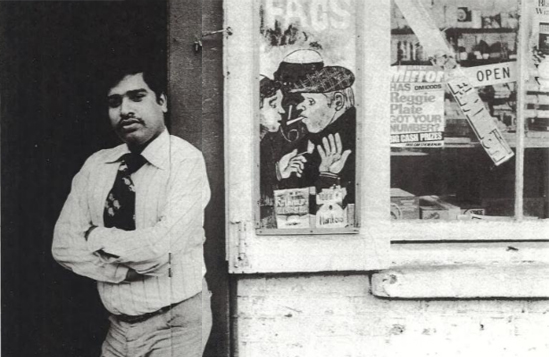

Abdus Salique, the spokesman for Dishari, came to this country from East Pakistan in 1970. He had been involved in pre-independence left-wing politics and found it wise to leave. In London’s East End he set up a small factory, added a newsagents and became involved in local Trades Council activities, always conscious of the needs of the Bangladeshi community in the area. Gradually he recognised the lack of a group. playing Bangladeshi music: ‘When I came to this country, I was aware that there were lots of Indian and Pakistani groups but none from Bangladesh, which was now independent, I thought I should do something about it especially when there was a lot of trouble in 1978 in Brick Lane (National Front racist attacks). I don’t play enough music to do something very creative but when I spoke with people they all asked me to do something. So I made this group, Dishari Shilpee Gosthi, which is a cultural organisation, with Esmael Shek the tabla player and Kadir Duvez the shahnai player and other musicians. A lot of people asked us to play and represent our country; we performed at many multi-cultural events, at a benefit at the Royal Albert Hall, on the TV programmes Skin and Nationwide, and at the Blair Peach memorial concert. Dan Jones, the secretary of the Trades Council, has been very helpful and I began to develop interest in Trade Union activities. Out of that I wrote the song to encourage my people to join the unions.’

|

‘Trade Union’ is certainly to the point — a mixture of folk song images and a blunt Eisler directness. Salique’s translation of the song goes as follows:

| |

We came from a distant land ( Counting the waves / of thirteen rivers and seven seas / With hopes of a better life. / We are the workers! / We labour in the factories and the workshops. / If we unite / We can grasp our rights in our hands. / Of course we must unite / If we want to defeat the racists / If we want to draw the teeth / Of those who suck our blood and exploit us. / We must stand together / Under the trade union banner. |

|

With its rhapsodic opening, the keening shahnai, the changes in rhythm and tone, the song is quite formal in its ballad-like structure and musically is rooted in the Bengali folk music tradition. Its message is neither the personal sentimentality of Victor Jara nor the pulpit thumping of the anti junta music of Theodorakis. It’s more in the vein of Joe Hill, Phil Ochs or Pete Seeger. It has an immediacy and a potent significance for the first and second generation Bangladeshis who lived through the racist attacks of the late ’70s, who struggle to survive in the declining rag trade and who have nurtured the stirrings of a fight-back consciousness.

A LONER IN ASIAN MUSIC

An integral part of the story of Dishari is the experience of Abdus Salique himself. In 1979 he was faced with a deportation order for illegal immigration. The resistance to that order was massive and petitions from the Bangladeshi community and intervention from the M.P. Peter Shore and others meant a strong case for Salique. Here Rough Trade re-enters, because a vital argument for Salique’s case was that he was due to make a record here and was therefore required in England. This helped to clinch it and the order was reversed. Salique intends to continue his political songs, hoping that an album can follow.

In many respects, ‘Trade Union’ stands out as something of a loner in the context of Asian music in general and Bengali music in particular. It is unlikely that Dishari would have been offered a recording contract by one of the big Asian labels involved in the thriving area of Asian film and pop music. Bangladesh is a younger, poorer nation and does not figure strongly and their music concerns itself with the relatively small Bangladeshi community in Britain.

Bengali music (the general cultural region of which Bangladesh is a part) has strong classical and folk traditions, with many songs derived from the poems of Rabindranath Tagore and folk songs in a pop style. But Salique stressed that his song was unique in that it dealt specifically with the problems faced by the Bangladeshi people here in Britain while the protest folk songs ‘at home’ revolved around harsher Third World circumstances. Musical influences here mean that Salique, an avid Top of the Pops watcher, wants to make music relevant for the young Bangladeshis growing up here.

| |

‘ I want to write and sing political songs based on the traditional folk songs but also to mix the traditional with new things. We live in Britain now and young people hear very different music around them. The Asian culture is very rich — we can create something new out of that, maybe using western instruments and styles.’ |

|

|